IN TIME - Cont'd

|

what circumstances! So that’s how me and my sister grew up. It was a kind of conflict between my mother’s voodoo and my father’s Marxism. A very fucked up family.” What wasn’t prophesized, however, was how the young Bland would soon be stricken by the power of music. “Tortured” by mother-inflicted piano lessons throughout his youth, Ed could never have predicted his first day of high school. “I was twelve and very concerned with what I was gonna do with my life—nothing particularly appealed. But then at Du Sable Freshman Day, the high-school band welcomed the Freshies. Well, the moment the band struck, a white light went off in my head; I said, ‘Ahhhh, this is it, this is what I want to do!’ So I went out of my way to plague the leader of the band. Sax was the instrument that interested me the most, but he said, ‘No, you have to start off on clarinet and take a talent test.’ I flunked it. And he says, ‘Your parents shouldn’t waste their money on a musical instrument. Go into another field!’ Well, the only thing I had going was I could read the treble clef, so I started with the beginners band, and my first teacher was the saxophonist Eugene Ammons.” Ammons, a senior at the school and hired via one of FDR’s New Deal programs, proved to be more interested in jamming with his peers than teaching, however. It wasn’t until another senior, Thelma Cotton, taught Bland how to properly breathe “both for life and the clarinet” that he began to excel. While he quickly went from an “F” student in beginners to a member of the senior band in a matter of months, his newfound success would be, unfortunately, short-lived. “There was a gang called the Four Corners who would beat up teachers and rob students, so I was a little concerned when they were gonna take my clarinet. I’d already had a razor up against my neck. See, my father wanted me to go to Du Sable, ’cause it was the second all-Black high school in Chicago. He wanted me to get that experience. Well, I got that experience!” Ed was allowed to move to the interracial Inglewood High School. Their music program couldn’t compare, but the lack of potential muggings allowed the budding musician to focus. And it paid off. A top symphony clarinetist gained wind of Bland’s playing and offered him free lessons. So the teenager would cross the color line of the Black-belt hood into his teacher’s White enclave, and in the course of three years became one of the city’s top clarinetists. School didn’t really seem to matter. “I hated school; it was just a place to practice.” Indeed, the real schooling happened at weekend jam sessions in which older folk like Art Tatum would flex their genius. Geniuses that, to Bland, even though he liked Basie and Goodman, didn’t incorporate “traditional” blues. “My father, since he was a Marxist, thought that folk music was music, of which I quickly disabused him. I didn’t understand the deep social and political ramifications at the time. I told him Leadbelly and all those people were pathetic.” In his young, cocky view, gospel faired no better. “Who needed that? Thomas A. Dorsey, the real father of gospel—this stuff was on street corners and in the churches of where I grew up. But hip jazz musicians, we’d call those church chords and any jazz musician who played like that was dissed! We were busy talking augmented elevenths and

82 waxpoetics |

what Tatum just played. I learned all kinds of tricks and maneuvers—these were stride pianists, so you know what type of technique they had—and they introduced me to Art and ultimately to Stravinsky.”

It was the last gasp of WWII and Bland was shipped to the Great Lakes, then San Francisco’s Treasure Island, where he was placed in the Navy band. In addition to playing the “Star Spangled Banner” punctually every morning, as well as officers’ dances (“it really became a bitch, ’cause the admirals were celebrating all the damn time”), Bland began fiddling with the baritone sax and exploring Schoenberg. Though challenging, he realized it was not an obvious commercial choice; besides, classical music raised other dilemmas. “You’re supposed to be happy to participate in the higher realms of Western culture, but what was to be happy about after this war we just went through?” After eighteen months of service, Bland was back in Chicago, looking for work and living with his mom, which, after she tried poisoning him with Clorox, lasted about three months. His father was also gone, having enlisted in the Army (at the age of thirty-seven) and fatally taking a bullet during the Battle of the Bulge. But the GI Bill enabled Ed to enroll in the lilywhite halls of the University of Chicago, where he studied music and philosophy. “I thought I would be able to study and argue with professors about musical theory, ’cause what had read didn’t make much sense. Eventually, I got kicked out.” The American Conservatory of Music picked him up, and, in 1949, while a part of the “52-20 Club” (unemploy-

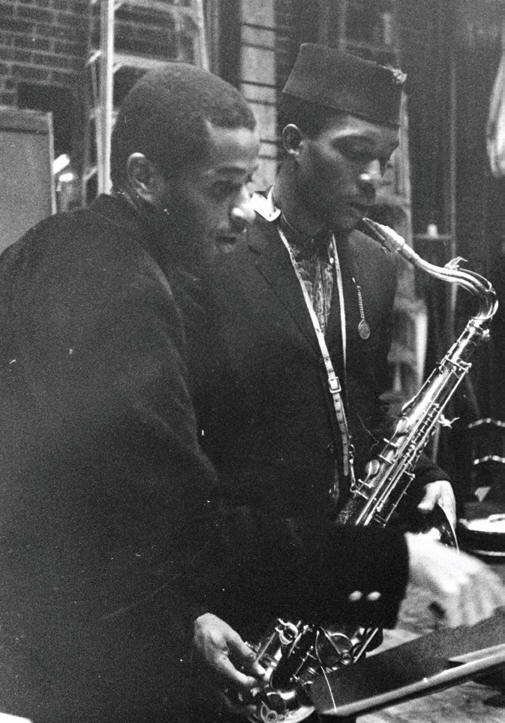

Ed Bland with Sun Ra saxophonist John Gilmore, 1961. Photograph by Helen Levitt. |

|

|