IN TIME

ED BLAND TRANSCENDED THE MOMENT WITH MUSIC AND FILM

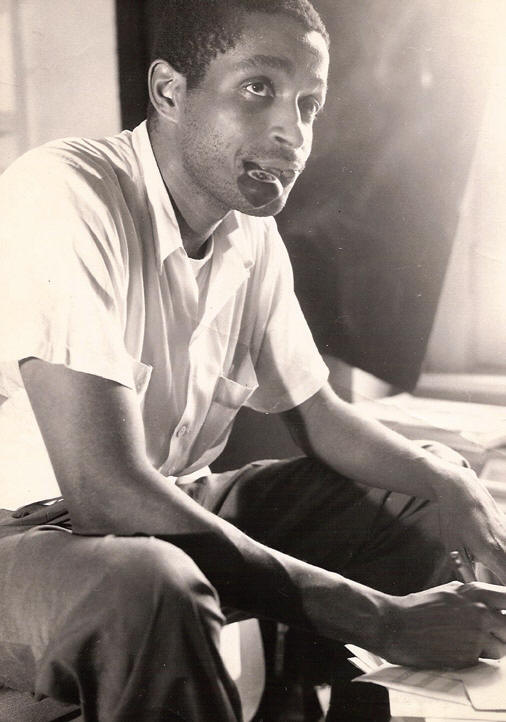

BY MATT ROGERS - PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE BLAND FAMILY

“THE SPIRIT OF JAZZ WI LL REMAKE SERIOUS MUSIC

BUT THE SOUNDS OF JAZZ WILL NOT BE USED.”

To say a person is “ahead of their time,” or that their body of work—be it pyramid-building, string theory, or bling-encrusted grills—is ahead of its time, is, agreed, inherently problematic and, like the use of the word “legendary,” damn cliché. For mere mortals lacking the benefit of an H. G. Wellsian time machine, how can anyone’s “time” be other than one’s, well, time? But if you track the fruitful career of one Edward O. Bland, you may be forgiven for mumbling such fluff. Try this exercise at home. Plot Art Tatum, Igor Stravinsky, Sun Ra, Jimmy McGriff, Batman and Robin, Diz, Country Joe, the Pazant Brothers, and Krzysztof Penderecki on a piece of paper. Now, if you can draw a straight line through said folk then maybe, just maybe, you’re ahead of your time too.

“These records that were done many a year ago, I considered, in terms of my writing, holding back,” says Bland on a recent visit to NYC. “ ’Cause it was commercial stuff, ultimately. Obviously, it wasn’t commercial the way many people thought of at the time.” It’s hard to know exactly what people thought of each stage of the now eighty-year-old composer/arranger/musician’s dynamic career—a career that on the surface appears to be a string of non sequiturs, an unforgettable equation of jazz, classical, gospel, rock, and funk. And then there’s Ed Bland, filmmaker, who, via his Cry of Jazz nearly five decades ago, squeezed into thirty-three minutes the essence of what Spike Lee and Ken Burns have taken many an hour to wring out. Oh, and he predicted the coming of this thing called hip-hop.

“The Negro is the only human American.”

Born on Chicago’s South Side in 1926 to a postal-working father and

spiritualist

mother, the young Edward never dreamt the arts, let alone music, would

ever hold any allure. “My father was self-educated and was a literary

critic. He made me, at seven years old, sit at meetings he would have at

home, in which Richard Wright would read some of his very first stories

he’d written when he came up from Mississippi. I thought [it was] a

waste of time, ’cause I should’ve been out playing baseball.” His

father’s job put food on table, but the bread and soup lines of the

Great Depression abounded. “My father was a Marxist, constantly

preaching to me the coming dictatorship of the proletariat, which

interested me to no extent whatsoever. You see, Langston Hughes, Ralph

Ellison, Gwendolyn Brooks, Ulysses Kay were all part of his posse, so to

speak. Then, on the other side of the house, was my mother, who was

constantly speaking to people who were deceased, telling her things that

would happen. Among some of the things prophesied was the death of my

father—when and under

WAXPOETICS 81